Camille Pissarro (1830-1903)

We Perform Camille Pissarro art authentication. Camille Pissarro appraisal. Camille Pissarro certificates of authenticity (COA). Camille Pissarro analysis, research, scientific tests, full art authentications. We will help you sell your Camille Pissarro or we will sell it for you.

People think of Camille Pissarro as the quintessential French rural landscapist, plodding about muddy fields in his smock. This is strange, as he was born and remained a Danish citizen. He was not even born in Europe. His father was a Portuguese Sephardic Jew, his mother a Creole, and he entered the world on the Danish Caribbean island of St. Thomas.

Pressed unwillingly into his father’s comprador business, Camille chafed at the bonds of colonial bourgeois life. In 1852 he left abruptly for Caracas with the Danish painter Fritz Melbye, from whom he received his first artistic tuition. Three years later he was in Paris. His father by this time had capitulated to his son’s desire for an artistic career, and Camille was assisted by the French branch of the family.

It was soon apparent that Pissarro was that rarity among artists, a tolerant, stable family man. He was also intellectual and gregarious, with an unusual gift for befriending fellow-artists. To this he added a unique gift: the capacity to remain friends with artists. Yet, by no means was Pissarro an appeaser or vacillator. On the contrary, he had strong opinions on art and at times castigated his fellows (for example Bonnard). But the artists he knew admired his steadfastness and integrity. And these were no ordinary artists; Corot, Courbet and Daubigny were his first major influences, then came Monet, Renoir, Degas, Sisley, Cezanne, Gaugin, Seurat and Signac. They comprised a truly formidable team, the younger members of which looked to the kindly Pissarro as their muse or guide.

Famously, Pissarro was the only Impressionist to exhibit at all eight Impressionist shows, yet he struggled to keep his large family. In the 1860’s they were close to poverty. Only in the last decade of his life did a measure of popular success come to him.

In the late 1850’s, Pissarro’s works were accepted by the Salon, but he was never quite able to join the Establishment. He could have easily done so. He had a command of academic realism, even though he had left formal schooling in favor of the Academie Suisse, a loose if prestigious body which allowed artists considerable freedom.

This pattern marks Pissarro’s whole life: he was psychologically an outsider. Always open to new ideas, in due course he became identified as anti-establishment. This no doubt affected his sales and kept him struggling long after lesser artists had succeeded commercially. Pissarro would not compromise his art for wordy gain, as much as he desired the latter.

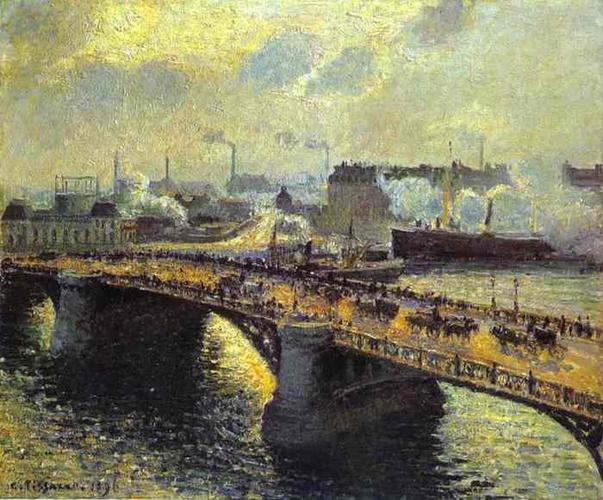

In 1870 he fled to London to escape the Franco-Prussian war. He lived in the unfashionable south-eastern suburbs and was charmed by them. Very few artists then or since have painted the serried ranks of middle class terraces at all, let alone with the affection that Pissarro expressed. Returning to France after the war, Pissarro was appalled to find that hundreds of his paintings had been used by invading Prussian troops as duckboards. Recovering from this blow, he led the Impressionist movement, developing Pointillism in the late 1880’s before returning to his earlier style. By the time he died, blind, in 1903, he was the grand old man of French painting, but an artist’s artist rather than a celebrity.

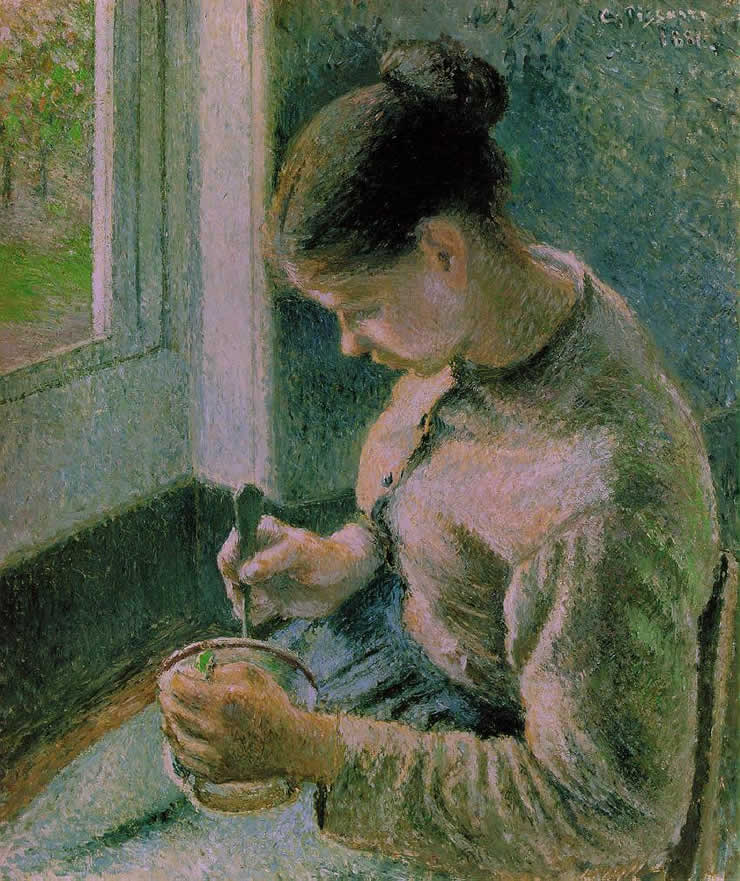

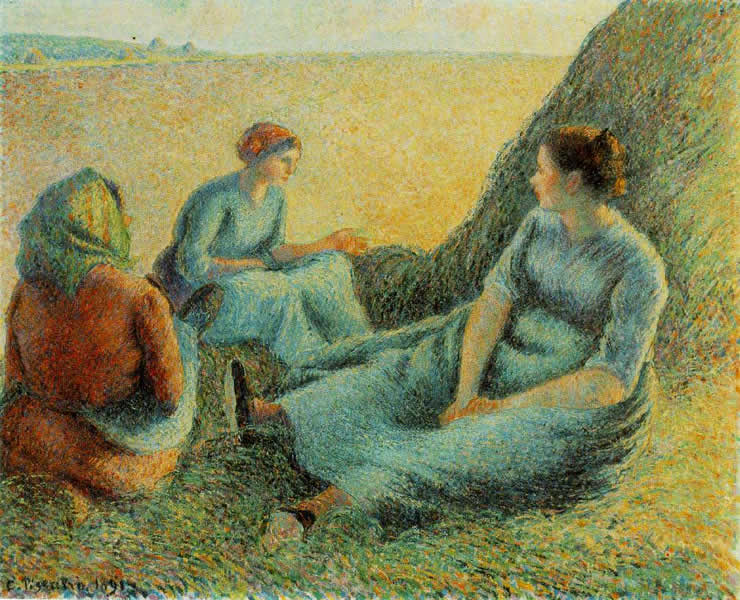

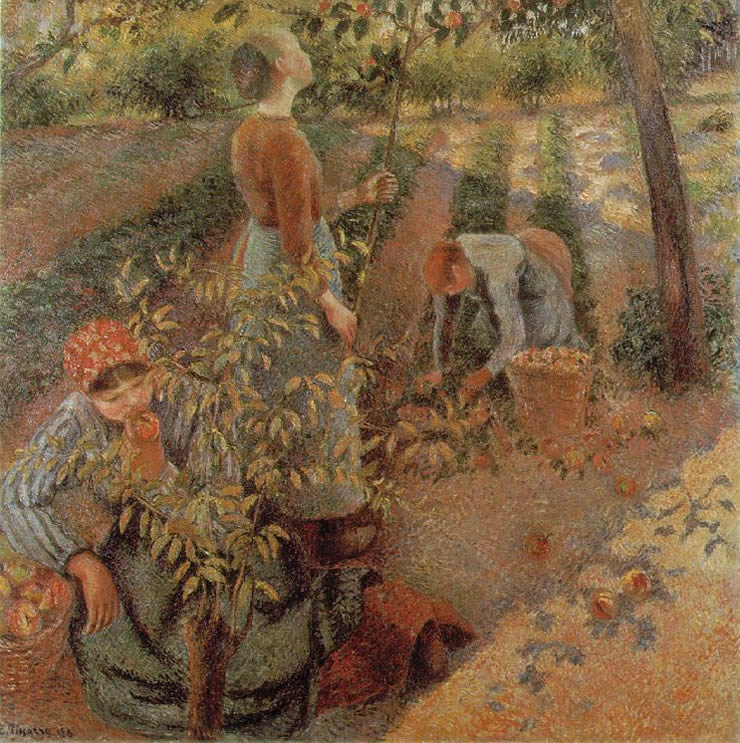

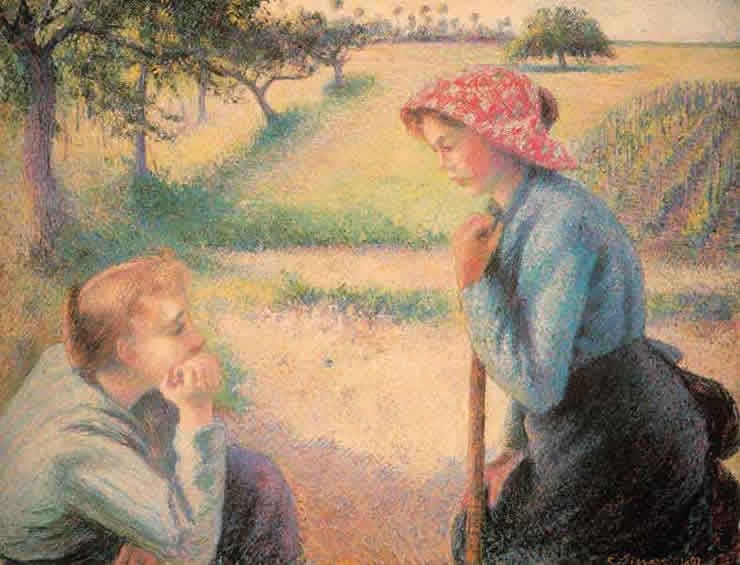

Pissarro hated sentimentality in art. The most corrupt art of all was sentimental art, he declaimed. His rural landscapes in their somber hues, free from the artifice of genre (which would have made his paintings far more saleable), were true to this unsentimentality. There’s a timelessness, directness and honesty about his landscapes. They haven’t dated like the plethora of smirking, flirting peasants who infest so much 19th century European art, mere creatures of the Boulevard painter’s fiscal imagination. Pissarro’s rural figures are plain, neither crushed nor elated by their quotidian lives. Rather they just get on with it, with understated strength and dignity.

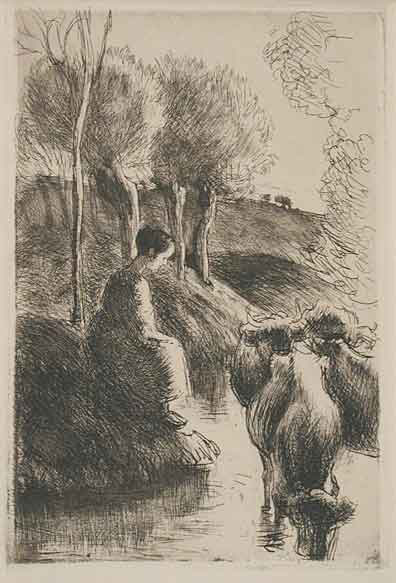

From an early date, Pissarro drew ordinary people going about their daily lives. In his time in Venezuela with Fritz Melbye the two of them would sketch interminably, recording the activities of the peasantry and townspeople they encountered. Pissarro filled sketchbooks with pencil and charcoal drawings of guitar players, cattle herders, and goose girls and so on. His early drawings presage his mature work: direct, unsentimental and descriptive. His later work is stripped of the detail and fussiness often apparent in his early drawings. A strong architectural line becomes dominant. Strength and simplicity are the hallmarks.

“Vachere au Bord de L’Eau” fits this description precisely. Done in pencil, charcoal and wash, the two figures are monumental, simple and strong. The implication is of timeless productive work, an understated tribute to the dignity of labour. The line is firm and assured, the quality of the representation high. The rudimentary, generic face of the woman is typical of Pissarro.

Note that in all but the most rudimentary drawings, Pissarro includes background -some sketchy trees, distant buildings, etc. – as are evident in the subject picture. Pissarro is invariably solving compositional questions in his drawing. These studies always point to more finished works, such as the gouache and watercolors shown below. Rarely does one find a figure study pure and simple. Further, the more finished, developed works follow exactly the same lines as the drawings: bold line, monumental figuring in the foreground, even when the foreground is crowded. He was said to have done watercolors and countless ink and pencil sketches, all signed Pizzarro (with a “Z” instead of an “S”, in the Spanish style). It is likely that some of these would be sketches of his memories of living in the Caribbean. He was probably the most prolific sketcher out of his contemporaries, creating four times as many as Manet and twice as many as Cezanne. Later sketches featured a look into the lives of the working class, some unsigned, so look for sketches that reflect the style of Pissarro, and depict the working class French.

The extreme change in Pissarro’s style from classical Impressionist to Divisionist and Pointilism is almost startling. His subjects remained the same, but his style drastically changed. One only has to look at “Woman Hanging Laundry” (1887) to see how Pissarro truly departed from his former style of painting. His earlier work was rigid and regimented, but through Impressionism he was able to paint with a looser feel.

Still wondering about an Impressionist landscape or composition hanging in your home? Contact us…it could be by Camille Pissarro.

Reviews

1,217 global ratings

5 Star

4 Star

3 Star

2 Star

1 Star

Your evaluation is very important to us. Thank you.