Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986)

Get a O’Keeffe Certificate of Authenticity for your painting (COA) for your O’Keeffe drawing.

For all your O’Keeffe artworks you need a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) in order to sell, to insure or to donate for a tax deduction.

Getting a O’Keeffe Certificate of Authenticity (COA) is easy. Just send us photos and dimensions and tell us what you know about the origin or history of your O’Keeffe painting or drawing.

If you want to sell your O’Keeffe painting or drawing use our selling services. We offer O’Keeffe selling help, selling advice, private treaty sales and full brokerage.

We have been authenticating O’Keeffe and issuing certificates of authenticity since 2002. We are recognized O’Keeffe experts and O’Keeffe certified appraisers. We issue COAs and appraisals for all O’Keeffe artworks.

Our O’Keeffe paintings and drawings authentications are accepted and respected worldwide.

Each COA is backed by in-depth research and analysis authentication reports.

The O’Keeffe certificates of authenticity we issue are based on solid, reliable and fully referenced art investigations, authentication research, analytical work and forensic studies.

We are available to examine your O’Keeffe painting or drawing anywhere in the world.

You will generally receive your certificates of authenticity and authentication report within two weeks. Some complicated cases with difficult to research O’Keeffe paintings or drawings take longer.

Our clients include O’Keeffe collectors, investors, tax authorities, insurance adjusters, appraisers, valuers, auctioneers, Federal agencies and many law firms.

We perform Georgia O’Keeffe art authentication, appraisal, certificates of authenticity (COA), analysis, research, scientific tests, full art authentications. We will help you sell your Georgia O’Keeffe or we will sell it for you.

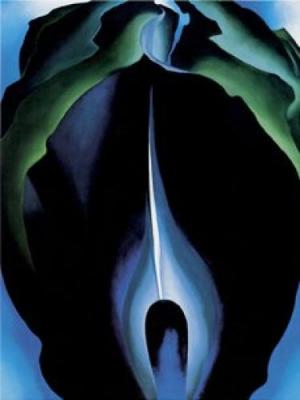

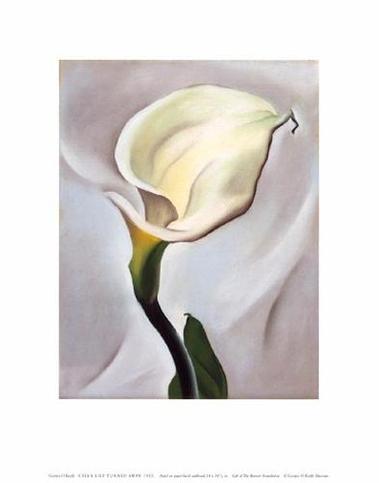

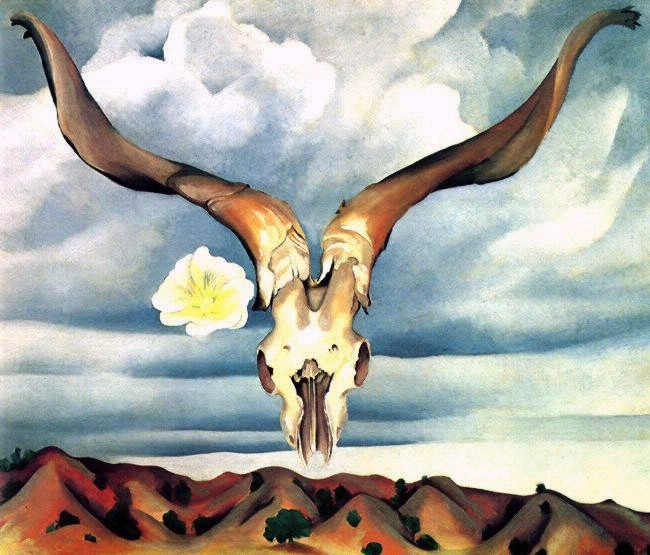

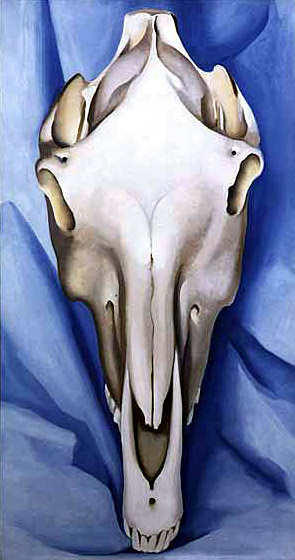

Georgia O’Keeffe was an American painter, who was famous for her abstract flower paintings and nature-themed compositions. She is considered to be one of the greatest painters of the 20th century, let alone one of the greatest female artists to ever have lived. She was famous for painting magnified, large-scale images of flowers as well as shells, leaves, bones, and landscapes of New Mexico.

O’Keeffe was born in Wisconsin to a family of dairy farmers. As a girl, she took watercolor courses from Sarah Mann, a local artist. Later, her family would move to Williamsburg, Virginia, and in 1905, O’Keeffe enrolled in the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1907, she moved to New York and studied at the Art Students League under the famous painter, William Merritt Chase.

In 1908, O’Keeffe moved back to Chicago where she found work as an illustrator. However, she became ill with measles in 1910 and moved back to Virginia to be with her family. From 1908 to 1912, it is said that O’Keeffe stopped painting completely. Apparently, she had an epiphany that she could not distinguish herself as a painter in the traditional academic style.

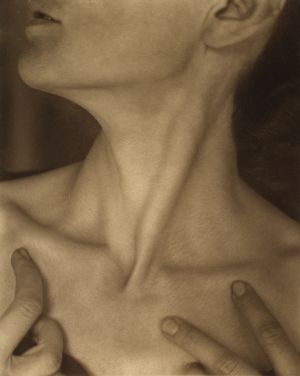

In 1912, O’Keeffe found inspiration to paint again after taking a summer class at the University of Virginia. She was introduced to the work of Arthur Wesley Dow and was encouraged to express herself on canvas through lines, color and shape. From 1912 to 1916, O’Keeffe would teach drawing at a number of schools in New York, South Carolina, and Texas. By 1916, O’Keeffe had fostered a relationship with her future husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz. O”Keeffe moved back to New York, and they married when his divorce from his first wife was finalized in 1924. She was often a model for Stieglitz, sometimes in the nude, and photos of her caused a sensation at his exhibitions.

O’Keeffe’s earliest work in New York, in the 1920s, featured her large-scale flower paintings. Most of these are painted as though the artist was looking at the subject close-up, as if through a magnifying glass. By this time, O’Keeffe had begun to paint primarily in oil, which was a major change considering that she had painted almost exclusively with watercolors throughout the 1910’s. With help from Stieglitz, her work gradually was exhibited every year, and by the later half of the 1920’s, O’Keeffe had earned a reputation as an important painter. She was extremely popular, and her paintings were highly sought-after and commanded even higher prices. In fact, a 1928 sale of six of her calla lily paintings for $25,000 was the largest sum ever commanded for a living American artist at that time.

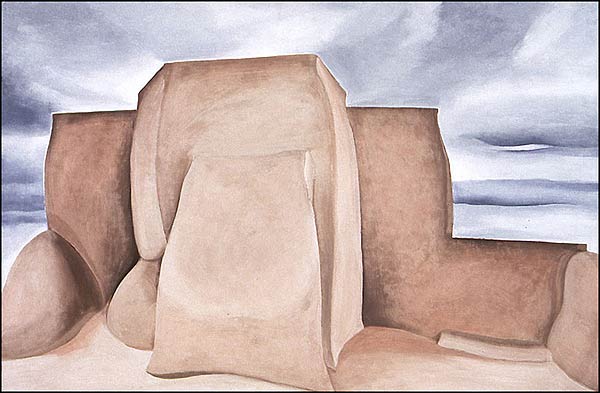

Other than her large-scale paintings of sensuous looking flowers, O’Keeffe is also known for her almost surrealist landscape paintings of the American Southwest. From 1929 until 1949, O’Keeffe visited Santa Fe and Taos, New Mexico often. On her journeys there, she collected and painted bones and was inspired by the beautiful colors of the desert.

O’Keeffe’s popularity continued to grow through the 1930s and 1940s, though a bout with illness again kept her from working through most of 1932, and she did not paint again until 1934. She had a number of one-woman exhibitions at this time, most notably at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1946, which was the first solo female exhibition the museum ever had. She also showed her work at the Whitney and at The Art Institute of Chicago. That same year, her husband died and after taking care of his estate, O’Keeffe settled in New Mexico permanently in 1949.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, O’Keeffe continued to paint in her adobe house in Abiquiu, New Mexico; however, by the early 1970s, her eyesight began to fail her. In 1973, O’Keeffe became friends with local potter Juan Hamilton who taught her how to work clay. Though her health was deteriorating, O’Keeffe continued to create art. She continued to work unassisted right up until she was 96 years old. Her last unassisted oil painting was created in 1972; watercolor in 1978; and graphite in 1984.

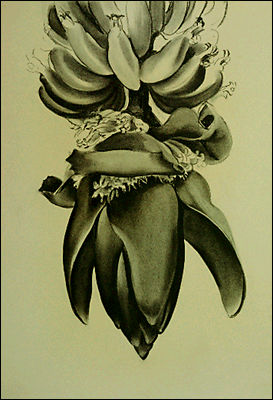

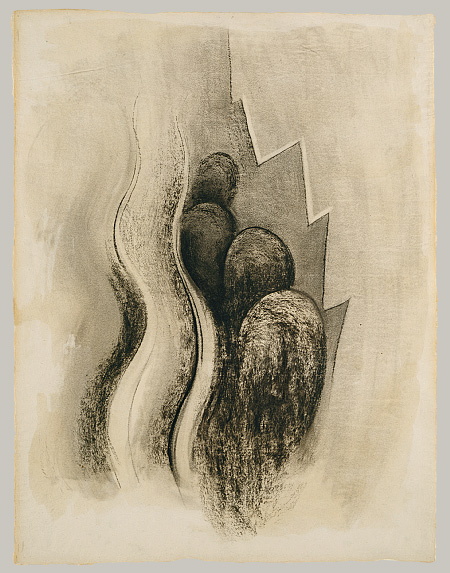

One of the most enduring mysteries about Georgia O’Keeffe that remains is her undiscovered works on paper. For reasons unknown, O’Keeffe had a hidden cache of drawings, pastels, watercolors, and charcoals that, until recently, were hidden from the public. Until recently, only a few of O’Keeffe’s works on paper had been seen by art scholars, so it had been assumed that O’Keeffe generally did not work on paper or simply threw her sketches out. These uncovered works now show that O’Keeffe had a lifelong love affair with sketching and working on paper and left a very extensive catalogue of them behind. Sketchbooks, floral pastels, abstract watercolors and more revealed a different side of O’Keeffe to art critics. It is said that after her death and at the closing of her estate, her drawers were overflowing with literally hundreds of sketches and watercolors.

Perhaps this new discovery of O’Keeffe’s works on paper is so surprising is because Stieglitz was a fervent promoter of her work, yet her works on paper were rarely exhibited until after his death. Surely, he would have tried to implore O’Keeffe to show these works, which are more than just practice sketches. However, some critics conclude that perhaps O’Keeffe and Stieglitz considered her watercolors to be of a lower class than her oil paintings, and in the best interest of her career, decided not to show them. Throughout her life, O’Keeffe retained an air of mystery about herself by dressing dramatically, not smiling in photos and being a generally reserved person. Perhaps in the end, O’Keeffe was just too shy to show these sketches and watercolors which showed her more spontaneous side. To O’Keeffe, these works must have been very special and private, and art lovers and critics are lucky to have access to them. Art collectors are also lucky because this new discovery means that perhaps a number of O’Keeffe’s sketches are still out there, unknown and otherwise unauthenticated from virtually any point in her artistic career.

Still wondering about that floral watercolor or sketch of a New Mexico landscape in your home? Contact us… we are the Georgia O’Keeffe experts.

Reviews

1,217 global ratings

5 Star

4 Star

3 Star

2 Star

1 Star

Your evaluation is very important to us. Thank you.