Edvard Munch (1863-1944)

Get a Munch Certificate of Authenticity for your painting or a COA for your Munch drawing, print or sculpture.

For all your Munch artworks you need a Certificate of Authenticity in order to sell, to insure or to donate for a tax deduction.

How to get a Munch Certificate of Authenticity is easy. Just send us photos and dimensions and tell us what you know about the origin or history of your Munch painting, drawing, print or sculpture.

If you want to sell your Munch painting, drawing, print or sculpture use our selling services. We offer Munch selling help, selling advice, private treaty sales and full brokerage.

We have been authenticating Munch and issuing certificates of authenticity since 2002. We are recognized Munch experts and Munch certified appraisers. We issue COAs and appraisals for all Munch artworks.

Our Munch paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures authentications are accepted and respected worldwide.

Each COA is backed by in-depth research and analysis authentication reports.

The Munch certificates of authenticity we issue are based on solid, reliable and fully referenced art investigations, authentication research, analytical work and forensic studies.

We are available to examine your Munch painting, drawing, print or sculpture anywhere in the world.

You will generally receive your certificates of authenticity and authentication report within two weeks. Some complicated cases with difficult to research Munch paintings, drawings or sculptures take longer.

Our clients include Munch collectors, investors, tax authorities, insurance adjusters, appraisers, valuers, auctioneers, Federal agencies and many law firms.

We perform Edvard Munch art authentication, appraisal, certificates of authenticity (COA), analysis, research, scientific tests, full art authentications. We will help you sell your Edvard Munch or we will sell it for you.

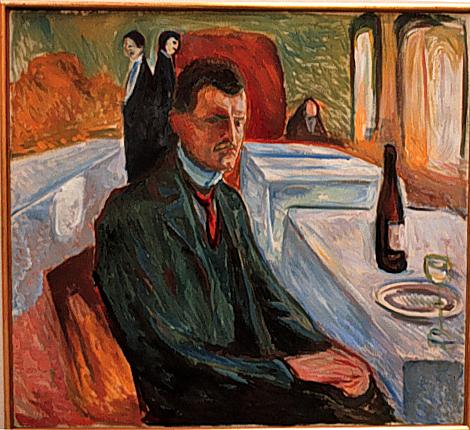

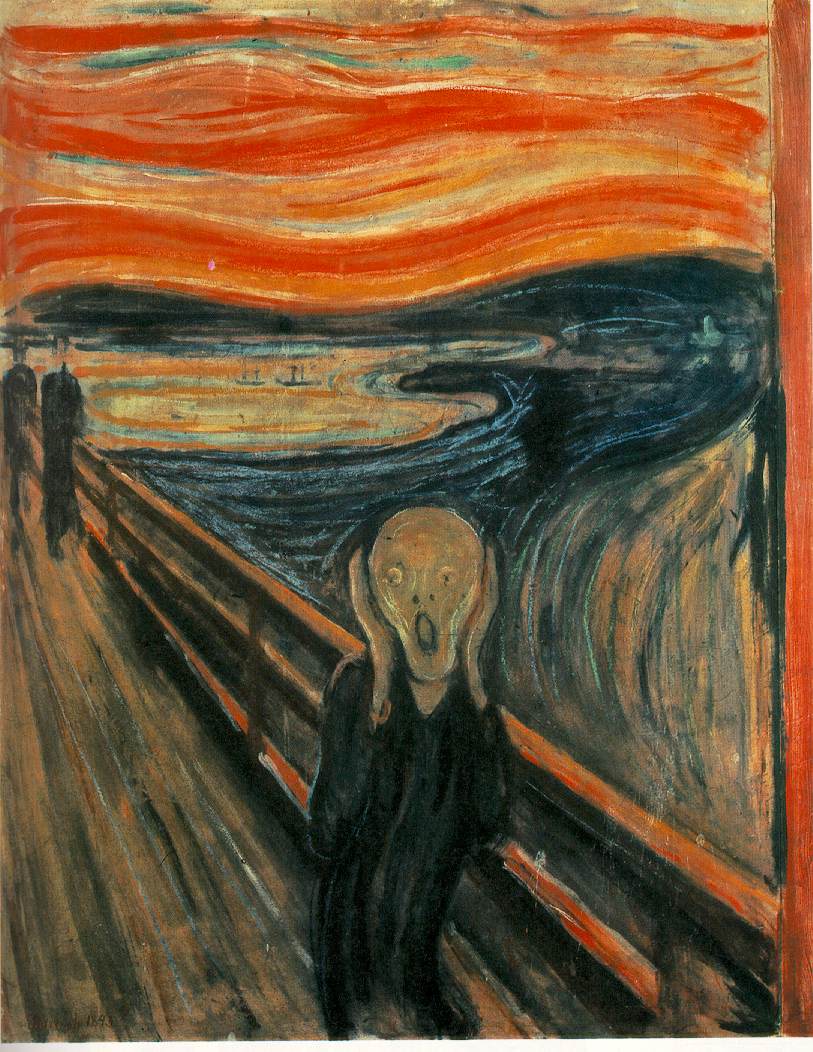

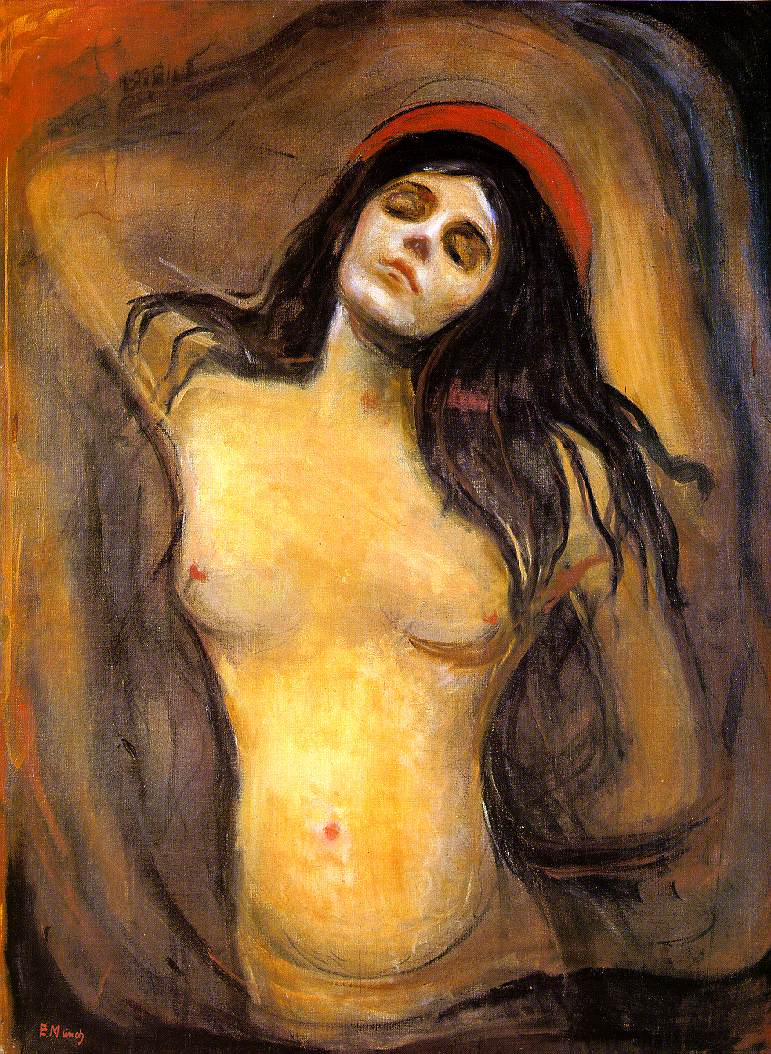

Edvard Munchwas a Norwegian Symbolist painter, printmaker, and an important forerunner of Expressionistic art. The Scream (1893; similar paintings include “Despair” and “Anxiety”), Munch’s best-known painting, is one of the pieces in a series titled The Frieze of Life, in which Munch explored the themes of life, love, fear, death, and melancholy. As with many of his works, he painted several versions of it.

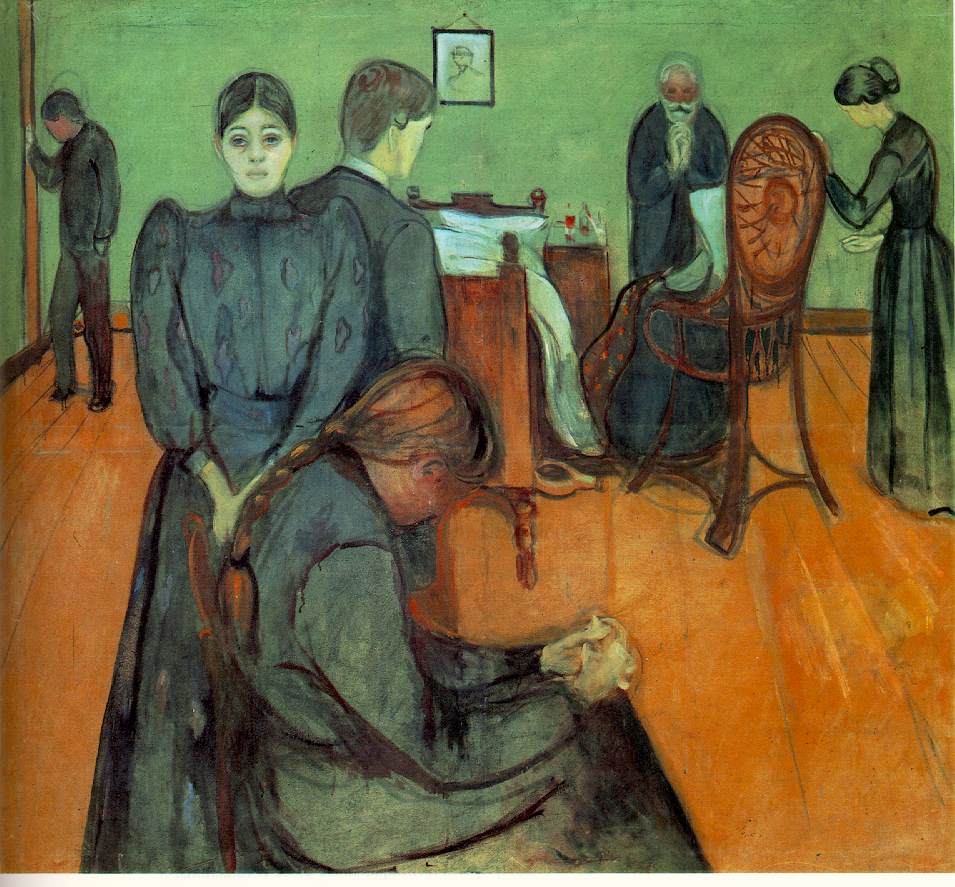

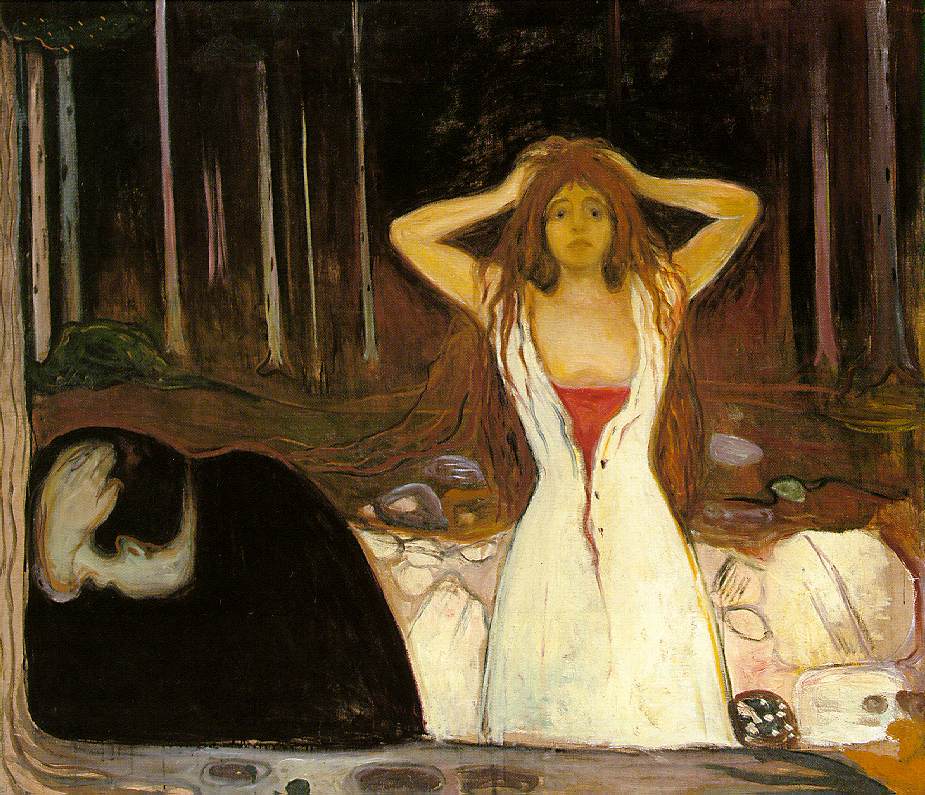

The Frieze of Life themes recur throughout Munch’s work, in paintings such as The Sick Child (1886, portrait of his deceased sister Sophie), Love and Pain (1893-94) though more commonly known as “Vampire.” Art critic Stanislaw Przybyszewski mistakenly interpreted the image as being vampiric in theme and content, and the description has since stuck, Ashes (1894), and The Bridge. The latter shows limp figures with featureless or hidden faces, over which loom the threatening shapes of heavy trees and brooding houses. Munch portrayed women either as frail, innocent sufferers (See “Puberty” and “Love and Pain”) or as the cause of great longing, jealousy and despair (See “Separation”, “Jealousy” and “Ashes”).

Some say these paintings reflect the artist’s sexual anxieties, though it could also be argued that they are a better representation of his turbulent relationship with love itself. Edvard Munch was born in Ådalsbruk, Norway, and grew up in Kristiania (now Oslo). He was related to painter Jacob Munch (1776-1839) and historian Peter Andreas Munch (1810-1863). He lost his mother, Laura Cathrine Munch, née Bjølstad, to tuberculosis in 1868, and his older and favorite sister Sophie (Johanne Sophie b. 1862) to the same disease in 1877. Ultimately his father, Christian Munch, died young, as well, in 1889. Munch also had a brother, (Peter) Andreas (b. 1865) and two younger sisters (Laura Cathrine b. 1867, Inger Marie b. 1868). After their mother’s death, the Munch siblings were raised by their father, who instilled in his children a deep-rooted fear by repeatedly telling them that if they sinned in any way, they would be doomed to hell without chance of pardon. One of Munch’s younger sisters was diagnosed with mental illness at an early age. Munch himself was also often ill. Of the five siblings only Andreas married, but he died a few months after the wedding. He would later say, “Sickness, insanity and death were the angels that surrounded my cradle and they have followed me throughout my life.”

In 1879, Munch enrolled in a technical college to study engineering, but frequent illnesses interrupted his studies. In 1880, he left the college to become a painter. In 1881, he enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design of Kristiania. His teachers were sculptor Julius Middelthun and naturalistic painter Christian Krohg. While stylistically influenced by the postimpressionists, Munch’s subject matter is symbolist in content, depicting a state of mind rather than an external reality. Munch maintained that the impressionist idiom did not suit his art. Interested in portraying not a random slice of reality, but situations brimming with emotional content and expressive energy, Munch carefully calculated his compositions to create a tense atmosphere.

Munch’s means of expression evolved throughout his life. In the 1880s, Munch’s idiom was both naturalistic, as seen in Portrait of Hans Jæger, and impressionistic, as in (Rue Lafayette). In 1892, Munch formulated his characteristic, and original, Synthetist aesthetic, as seen in Melancholy, in which color is the symbol-laden element. Painted in 1893, The Scream is his most famous work.

During the 1890s, Munch favoured a shallow pictorial space, a minimal backdrop for his frontal figures. Since poses were chosen to produce the most convincing images of states of mind and psychological conditions (Ashes), the figures impart a monumental, static quality. Munch’s figures appear to play roles on a theatre stage (Death in the Sick-Room), whose pantomime of fixed postures signify various emotions; since each character embodies a single psychological dimension, as in The Scream, Munch’s men and women appear more symbolic than realistic.

In 1892, the Union of Berlin Artists invited Munch to exhibit at its November exhibition. His paintings evoked bitter controversy, and after one week the exhibition closed. In Berlin, Munch involved himself in an international circle of writers, artists and critics, including the Swedish dramatist August Strindberg. While in Berlin at the turn of the century, Munch experimented with a variety of new media (photography, lithography, and woodcuts), in many instances re-working his older imagery. One of his great supporters in Berlin was Walter Rathenau, later the German foreign minister, who greatly contributed to his success.

In the autumn of 1908, Munch’s anxiety became acute and he entered the clinic of Dr. Daniel Jacobsen. The therapy Munch received in hospital changed his personality, and after returning to Norway in 1909 he showed more interest in nature subjects, and his work became more colorful and less pessimistic. In the 1930s and 1940s, the National Socialists labeled his work “degenerate art”, and removed his work from German museums. This deeply hurt Munch, who had come to feel Germany was his second homeland.

Munch built himself a studio and simple house at Ekly estate, at Skøyen, Oslo, and spent the last decades of his life there. He died there on January 23, 1944, about a month after his 80th birthday. He left 1,000 paintings, 15,400 prints, 4,500 drawings and watercolors, and six sculptures to the city of Oslo, which built the Munch Museum at Tøyen. The museum houses the broadest collection of his works. His works are also represented in major museums and galleries in Norway and abroad. Munch appears on the Norwegian 1,000 Kroner note along with pictures inspired by his artwork.

“From my rotting body, flowers shall grow and I am in them and that is eternity.” —Edvard Munch

Munch Discovery

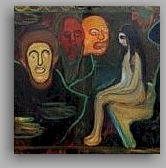

The Bremen Kunsthalle art museum on Friday put on display a previously unknown painting by Norwegian master Edvard Munch, depicting a naked girl appearing to be threatened by a vision of the faces of three men.

Museum director Wulf Herzogenrath said the painting could be interpreted as depicting the fears of a girl in her puberty about the male sex.

The Kunsthalle titled the painting ‘Girl and Three Men’s Heads’. Three men’s faces appear to be dancing like masks in front of a shy and withdrawn girl sitting naked on a chair.

Herzogenrath spoke of the “sensational find” in describing how the painting was discovered while restoration work was being done on the Munch painting ‘The Dead Mother’.

Restorers happened to discover the second canvas beneath ‘The Dead Mother’ canvas. The museum commissioned Art Certification Experts and historians to examine it, with their verdict being that the painting was also by Munch (1863-1944).

The symbolist-style painting, measuring 90 by 100 centimeters, is estimated by Art Certification Experts to date to around 1898.

“The work is a wonderful new picture for humankind,” Herzogenrath said, while recalling the theft of two Munch paintings at the Oslo art museum, including the famous ‘The Scream’, in August 2004.

“Humankind has lost two Munch pictures…and now humankind has gained a new painting thanks to academic research,” he said.

Bremer Kunsthalle art historian Barbara Nierhoff said there was no doubt about the authenticity of the painting being by Munch, as both the subject matter and style of the discovered painting fit into the painter’s oeuvre. Among others, there was the painting ‘Puberty’ from 1893 showing a naked girl being threatened by a shadowy figure.

Still wondering about a late 19th or early 20th century Norwegian painting in your family collection? Contact us…it could be by Edvard Munch.

Reviews

1,217 global ratings

5 Star

4 Star

3 Star

2 Star

1 Star

Your evaluation is very important to us. Thank you.