Zelda Fitzgerald

Get a Fitzgerald Certificate of Authenticity for your painting (COA) for your Fitzgerald drawing.

For all your Fitzgerald artworks you need a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) in order to sell, to insure or to donate for a tax deduction.

Getting a Fitzgerald Certificate of Authenticity (COA) is easy. Just send us photos and dimensions and tell us what you know about the origin or history of your Fitzgerald painting or drawing.

If you want to sell your Fitzgerald painting or drawing use our selling services. We offer Fitzgerald selling help, selling advice, private treaty sales and full brokerage.

We have been authenticating Fitzgerald and issuing certificates of authenticity since 2002. We are recognized Fitzgerald experts and Fitzgerald certified appraisers. We issue COAs and appraisals for all Fitzgerald artworks.

Our Fitzgerald paintings and drawings authentications are accepted and respected worldwide.

Each COA is backed by in-depth research and analysis authentication reports.

The Fitzgerald certificates of authenticity we issue are based on solid, reliable and fully referenced art investigations, authentication research, analytical work and forensic studies.

We are available to examine your Fitzgerald painting or drawing anywhere in the world.

You will generally receive your certificates of authenticity and authentication report within two weeks. Some complicated cases with difficult to research Fitzgerald paintings or drawings take longer.

Our clients include Fitzgerald collectors, investors, tax authorities, insurance adjusters, appraisers, valuers, auctioneers, Federal agencies and many law firms.

We perform Zelda Fitzgerald art authentication, appraisal, certificates of authenticity (COA), analysis, research, scientific tests, full art authentications. We will help you sell your Zelda Fitzgerald or we will sell it for you.

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, born Zelda Sayre in Montgomery, Alabama, was a painter, novelist and the wife of writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, whom she married in 1920. Her husband dubbed her “the first American Flapper.” She published an autobiographical novel, Save Me the Waltz, in 1932. In June 1930 she suffered her first mental breakdown; soon afterwards, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia and was required to live from then on in a mental hospital. She died at the age of 47 in a fire at the Highland Mental Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina.

Born in 1900, Zelda was the youngest of six children. Her mother, Minnie Sayre, named her after a Gypsy queen in a novel. She was totally indulged by her mother, who spoiled her, but her father, a justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama and one of Alabama’s leading jurists, was a stern and remote man. As a child she was extremely active; she danced, took ballet lessons and enjoyed the outdoors.

In 1914 Zelda began attending Sidney Lanier High school. She was bright but uninterested in her studies. Her ballet lessons continued into high school. During these years, she began an active social life. She earned a reputation as a “speed.” She drank, smoked and spent time alone with boys. In a newspaper article about one of her dance performances, she is quoted as saying that she only cared about “boys and swimming.” Her father’s reputation was the only thing that saved her from social ruin.

As a southern woman growing up around the turn of the century, Zelda’s shameless antics were frowned upon to say the least. Southern women were expected to be delicate, docile and accommodating. Zelda commented on her struggle to be who she needed to be while living under stifling social pressures.

“It’s very difficult to be two people at once, one who wants to have a law unto itself and the other who want to keep all the nice old things and be loved and safe and protected.”

Zelda met Scott Fitzgerald in 1918 while he was stationed at an army post near Montgomery. They met at a Montgomery country club where she performed the “Dance of the Hours.” They began a courtship that was interrupted in 1919 when Scott was discharged from the military and returned to New York to build a life for himself and Zelda.

The two wrote to each other frequently and in March of 1919 Scott sent Zelda his mother’s ring and the two became engaged. Many of Zelda’s friends and members of her family were wary of the relationship. They did not approve of Scott’s excessive drinking habits, and her Episcopalian family did not like that he was a Catholic. The two married in April 1920.

Once they married, Zelda was expected to be the witty and charming wife of an up-and-coming writer. After Scott published This Side of Paradise, the two were the focus of media attention as much for their drunken antics as Scott’s talent. Jealousy plagued their marriage. Zelda was jealous of Scott’s literary success. Scott felt alienated by all of the male attention she received. Their excessive drinking often caused fights to get out of hand. There is some evidence that Scott became physically violent toward Zelda during drunken arguments.

But the endless round of parties and the massive quantities of alcohol they consumed began to take a toll on the couple’s health and relationship, and they squandered virtually all the money Scott made from his writing, spending as much as US$30,000 per year — a colossal figure for the time. By the mid-Twenties Scott had become a notoriously heavy drinker (he even had his own private bootlegger, and when not writing he would typically binge-drink until he passed out and was sent home in a taxi).

While living in Paris, Scott Fitzgerald — by then an international literary star — met rising American author Ernest Hemingway, whose career he did much to promote. Hemingway and Fitzgerald became firm friends (although they later became estranged), but as biographer Nancy Milford reports, Zelda disliked Hemingway from the start, openly describing him as “bogus” and “as phoney as a rubber check”, and considered Hemingway’s domineering macho persona to be merely a posture. One of the most serious rifts between Zelda and Scott took place because Zelda became convinced (albeit with no credible evidence) that Hemingway was “a fairy” and that he and Scott were having a homosexual affair. For the most part, Zelda’s dislike for Hemingway was perhaps due to jealousy — she once threw herself down a flight of marble stairs at a party because Scott, engrossed in talking to Isadora Duncan, was ignoring her.

The birth of their only child, Frances “Scottie” Fitzgerald in 1921 did little to slow the pace of their lives, and although Zelda was fond of the child and wrote to her frequently, Scottie was almost entirely brought up by nannies and was often apart from her parents.

In 1924, during one of the first of their several trips to France, Zelda had a brief affair (or at least became infatuated) with a dashing young French pilot, Edouard Jozan. This prompted her husband to lock her in their house to keep her from seeing him again; later, they would embellish the story by claiming that Jozan had committed suicide. It is possible that Zelda’s long descent into schizophrenia began during this period. She wrote a number of short stories beginning in 1925, but many of these were published under Scott’s name, another possible factor of her growing discontent; three other stories, written just before her first breakdown, were later lost.

Scott drew heavily upon his wife intense personality in his writings, often directly quoting segments from her personal diaries in his work. She never commented on this, other than a pithy remark in a review that òIt seems to me that on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and also scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald ñ I believe that is how he spells his name ñ seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.

While in Paris, at age 27, Zelda became obsessed with ballet, which she had studied as a girl. She had been praised for her dancing skills as a child, and although the opinions of their friends vary as to her skill, it appears that she did have a fair degree of talent. But Scott was totally dismissive of his wife’s desire to become a professional dancer, considering it a waste of time.

Ironically, much of the conflict between them stemmed from the boredom and isolation Zelda experienced when Scott was writing — she would often interrupt him when he was working. Scott conversely became increasingly determined to keep Zelda at home, presumably because he feared that she might begin another affair. Zelda evidently had a deep desire to develop a talent that was entirely her own, perhaps a reaction to Scott’s fame and success as a writer.

Sadly, she rekindled her studies too late in life to become a truly exceptional dancer, but she obsessively insisted on grueling daily practice (up to eight hours a day) that contributed to her subsequent physical and mental exhaustion. Her eventual breakdown included elements of obsessive-compulsive disorder. In 1930, she was admitted to a sanatorium in France where, after months of observation and treatment and a consultation with one of Europe’s leading psychiatrists, she was officially diagnosed as having schizophrenia. However, her last psychiatrist, Dr. Irving Pine, believed (too late) that she may have actually had severe untreated bipolar disorder. He speculated after her death that the cause of her breakdowns may have been as much from her husband’s mental bullying and her treatment for her disorder as the disorder itself.

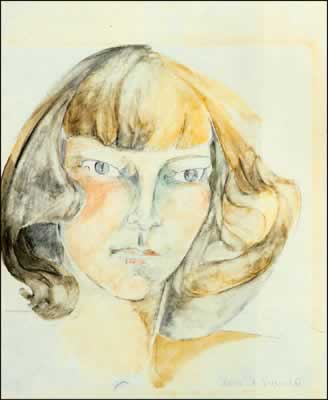

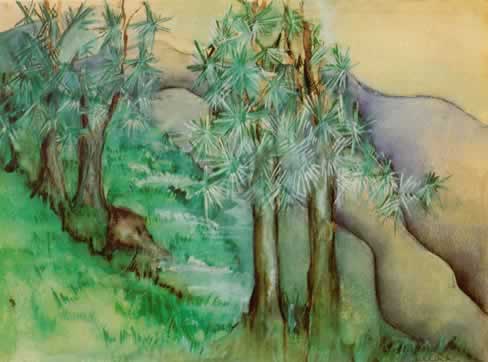

Zelda Fitzgerald spent the remaining 18 years of her life in various stages of mental distress. However, in her few periods of lucidity, she composed some of her best work, including her only novel, Save Me the Waltz, and numerous abstract paintings. She died in 1948, with her few remaining unpublished bits of work, her last letters to Scott before he died the last remnants of her life. At the time of her death, she was writing a second novel, Caesar’s Things, when a fire consumed the sanitarium where she lived in Asheville, North Carolina.

Although her status as the wife of a great American writer and socialite, as well as her sad decline of mental health are perhaps what people remember most about Zelda, it is her artwork that has become her legacy. She so yearned to have a talent of her own during her lifetime to match her husband, and art historians and experts can now recognize that talent.

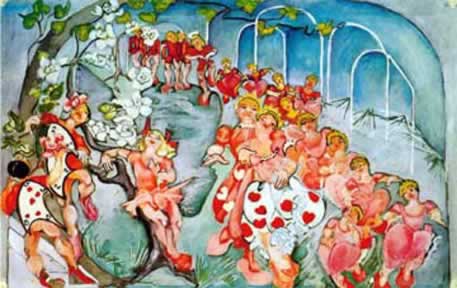

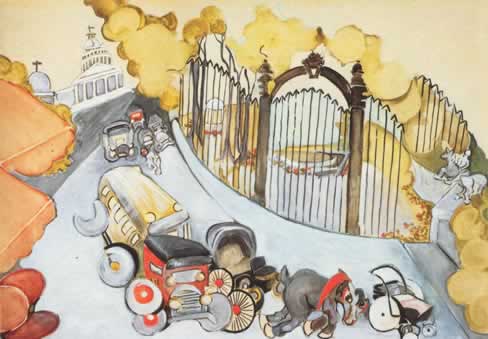

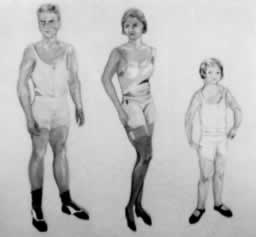

Among her oeuvre were countless watercolors and even detailed paper dolls. Typically featuring storybook and mythological scenes, Zelda Expressionist/Surrealist style was no doubt a reflection of the state of her mental health. It is likely that she was self-taught, or took informal painting instruction from known Parisian or American painters of the early 20th century. Because of her husband fame, it is most certain that she rubbed elbows with famous artists of the day. Her style is vaguely reminiscent of the Surrealist artist Salvador Dali, and it is possible that she either drew inspiration or took instruction from him. Sadly, we may never know how many paintings, sketches or other works of art or writing of hers were lost in the fire that also took her life.

Still wondering about a painting in your family collection? Contact us…it could be by Zelda Fitzgerald.

Reviews

1,217 global ratings

5 Star

4 Star

3 Star

2 Star

1 Star

Your evaluation is very important to us. Thank you.