Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902)

Get a Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) Certificate of Authenticity for your painting (COA) for your Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) drawing.

For all your Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) artworks you need a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) in order to sell, to insure or to donate for a tax deduction.

Getting a Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) Certificate of Authenticity (COA) is easy. Just send us photos and dimensions and tell us what you know about the origin or history of your Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) painting or drawing.

If you want to sell your Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) painting or drawing use our selling services. We offer Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) selling help, selling advice, private treaty sales and full brokerage.

We have been authenticating Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) and issuing certificates of authenticity since 2002. We are recognized Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) experts and Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) certified appraisers. We issue COAs and appraisals for all Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) artworks.

Our Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) paintings and drawings authentications are accepted and respected worldwide.

Each COA is backed by in-depth research and analysis authentication reports.

The Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) certificates of authenticity we issue are based on solid, reliable and fully referenced art investigations, authentication research, analytical work and forensic studies.

We are available to examine your Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) painting or drawing anywhere in the world.

You will generally receive your certificates of authenticity and authentication report within two weeks. Some complicated cases with difficult to research Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) paintings or drawings take longer.

Our clients include Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) collectors, investors, tax authorities, insurance adjusters, appraisers, valuers, auctioneers, Federal agencies and many law firms.

We perform Bierstadt art authentication, appraisal, certificates of authenticity (COA), analysis, research, scientific tests, full art authentications. We will help you sell your Bierstadt or we will sell it for you.

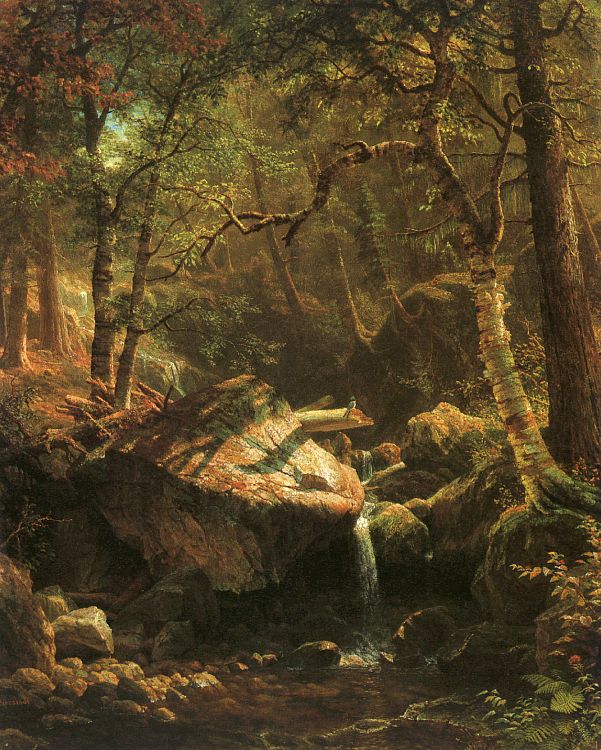

German-born, Bierstadt moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts with his family at the age of two. He returned to Düsseldorf, Germany in 1853 and studied painting there until 1857. That year, he returned to New Bedford and organized an exhibition featuring his work as well as other artists. This was the launching point of Bierstadt’s career, a man who would become known as the foremost painter of the American west.

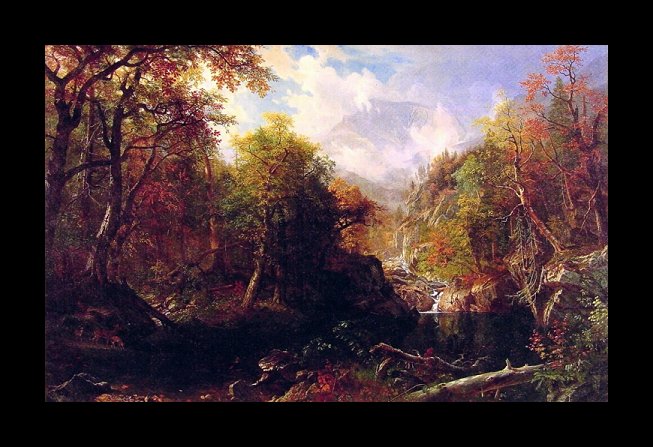

Almost completely a landscape painter, Bierstadt wowed the Eastern United States with his giant oil paintings of the west. He became internationally famous for his sweeping panoramas of the pristine western wilderness. His work of the west brought in extremely high prices for the day, in both public and private collections.

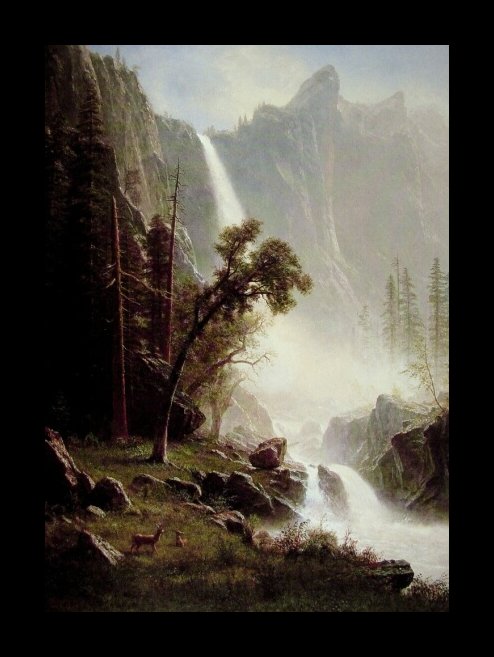

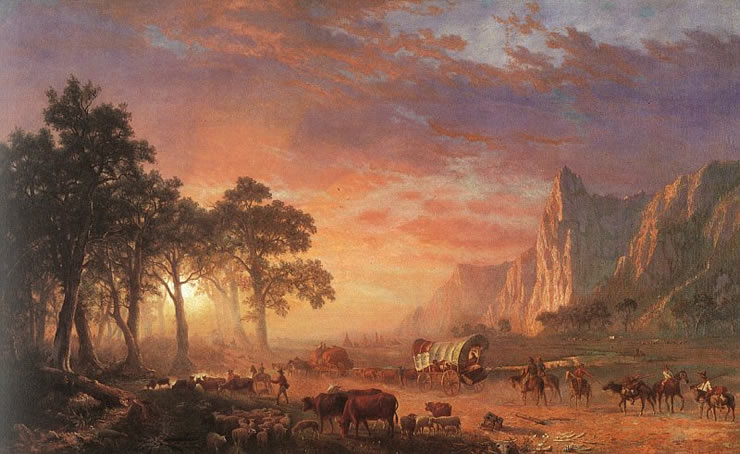

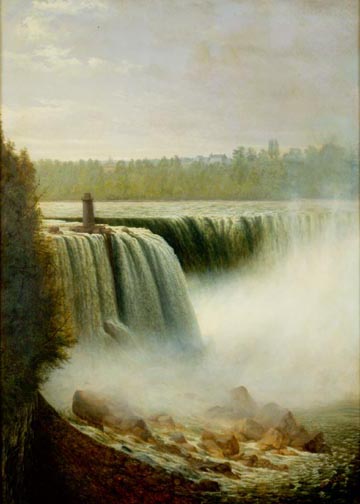

Bierstadt’s oil paintings would produce a beautiful golden light that no digital artist could equally recreate today. While his subjects were often breathtaking enough (Yosemite, the Pacific north, Niagara Falls and mountains) it was his style that brought the west to life. Easterners would be in awe of his work, and many would describe them as having a “religious” or “ethereal” value. The spray of a waterfall or the glow of a sunset through the mountains created a transcendental feel to those who had never seen the beauty of the west before. These are reflected in such works as “Bridal Veil Falls, Yosemite” (1871-1873).

Aside from their beauty, Bierstadt’s paintings were also behemoth in comparison to most other canvases. In order to fully capture the panorama of wide open, pristine nature, Bierstadt would often paint on an unusually large scale. One of his most famous works “The Emerald Pool” (1870) measures in at more than 76in tall x 119in long (about 6 x 10 feet). If there is a fairly large painting of the west in your parlor, it is highly likely that it was painted by Albert Bierstadt.

Bierstadt can only be described as a realist landscape painter, and his attention to detail is remarkable. While people and animals often appear as part of his backdrop, and not as the subject, he still gave them crisp details and features. A great example is one of his early paintings done in Europe, “The Arch of Octavius” (1858). A cat scampers across the foreground of this scene, people are mingling in a marketplace, yet the arch itself is the most dominant object in the painting. He would also paint American Indians and their homes and artifacts in his paintings, but they too would serve more as a backdrop than a subject.

His brother, Edward, was a photographer, and Bierstadt worked in that medium as well, though his photography is not as well archived or housed in museums. On his trips to the west, he would take photos to help him remember what he wanted to paint when he would return to his studio in New York. Where are these photos that Bierstadt took? They would serve as great historic and artistic value as an accompaniment to the paintings that were produced from them. He was also known to make sketches during these wagon trips west of what he saw, and they would also be valuable if found and verified as Bierstadt’s.

Bierstadt was very ambitious, and a relentless marketer of his own work, acquirer of awards, collector of commissions and seeker of endorsements. He did this on both sides of the Atlantic. When his popularity waned in America, he went to Europe and opened studios, etc. He wrote to everyone imaginable trying to get his name in every conceivable published, well-distributed directory of artists. Also he got himself appointed the head of various official sounding “departments” at fairs around the country. I’ve never seen such blatant careerism in a nineteenth century artist. He was extremely good at getting newspaper coverage every time he sneezed and made a then-record sale of “The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak,” for $25,000 in winter 1865.

In 1882, his studio in Irvington, New York was destroyed in a fire and many of valuable paintings were lost. This too leaves a wide-open possibility of some of his work surviving the fire (possibly from looters) or that some were saved in fragments. In 1893 he wrote to President Cleveland: [this without corrections of misspellings] “Give us free Art, good pictures we are not afraid of, it is the imitations, counterfits that injure not only the Artist but the buyer.”

Bierstadt and his second wife made a trip to the European Alps in summer 1895, also in 1896 they went to Lucerne and Budapest. In 1896 he wrote to his family that he might move back to Europe permanently. In 1897 he and his wife returned to Geneva and other parts of Switzerland. Bierstadt got a patent in 1895 on a “railway car” that could also be converted into a church or a fort. Sadly, his invention was never manufactured or marketed. In 1899, Bierstadt tried to convince President McKinley that the U.S. government should buy a castle on Corfu–Achillon, that belonged to the Empress of Austria. Bierstadt thought we should give it to Queen Victoria to prevent her from taking her holidays in France.

While Bierstadt’s catalog generally consists of landscapes of the west (more than 400 on record), he must have done many other lesser-known paintings before them while studying in Europe. Where are they, and what could they contain? His “Arch of Octavius” has been put under scrutiny for bearing anti-Catholic symbolism as well as symbolism about emigrants. Could Bierstadt have made other such symbolic paintings while in his youth in Europe?

Similarly, the painting “Mount Shasta” by fellow artist Ferdinand Schafer has caused speculation in the art world because it bears such a resemblance to other paintings of Mount Shasta by Albert Bierstadt. So close, in fact, that one of Schafer’s paintings was initially attributed to Bierstadt in 1964 after being acquired by the Oakland Museum. The two artists even signed their work similarly.

Toward the end of his career, French Impressionism started to become popular, and the demand for his work declined. Despite the staggering amount of money his paintings brought in, he declared bankruptcy in 1895. Today, his work is housed all over the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum, as well as the Capitol building in Washington D.C.

Reviews

1,217 global ratings

5 Star

4 Star

3 Star

2 Star

1 Star

Your evaluation is very important to us. Thank you.